The Limits of Narrative Fluency

Does narrative fluency solve the problems it sets out to?

In a world bereft of epistemological signposts, who should you trust?

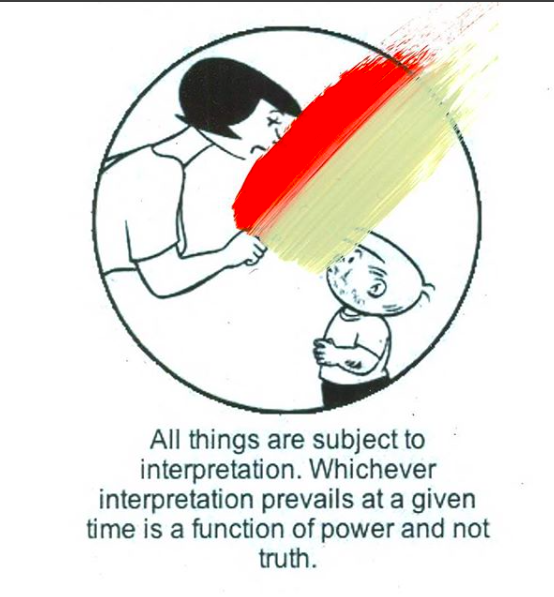

Nietzsche, by way of The Far Side, by way of a now-deleted Tumblr post

The pedagogical currents described above aim for what I’ve been calling narrative fluency: the receptive ability to tease arguments apart and examine their evidential bases, plus the productive ability to weave together original arguments using facts (or “facts”) and language. Far be it from me to deny the value of skills like historical thinking and web design. If I were advising a high-school civics teacher or history department chair today, and if they assured me that my ideals wouldn’t be drowned under the practical challenges of teaching, I would likely tell them to draw from many of the pedagogical streams I’ve discussed. For all their limitations, creative pedagogies involving contemporary problems and real media handily beat traditional facts-only teaching. Nonetheless, let me voice two broad concerns about narrative fluency.

The first is that serial exercises in critical thinking can engender a kind of epistemological complacency. After the professors publish their op-eds, after the students grade them on the media-literacy rubric, after MOGEF passes the most rigorous vetting—even in the face of all this evidence, Jun-ho’s mind may remain unchanged. And if someone should then challenge his beliefs, Jun-ho can now say, “I’ve looked at all the facts and studies. Have you? No? Then clearly I’m not the one who needs to give things a second thought.” Narrative fluency wants to be a process for overturning our long-held assumptions, but it can just as easily become an excuse for stubbornness.

At the heart of the critical-thinking discourse lies a spiritual belief that if we only think hard enough, we will arrive at objective truth. But how do we know when we’ve thought hard enough? The only way we can be sure that narrative-fluency pedagogy is working is when it guides people to the conclusions we have already decided they ought to reach. Those who maintain fringe views despite the teacher’s best efforts force us to backtrack and ask what went wrong. Perhaps we didn’t engage with the counterargument thoroughly. Perhaps the sources lacked diversity. Perhaps Jun-ho just isn’t getting it. In any case, narrative fluency gets to measure its own yardstick.

My greatest concern about narrative fluency, then, has to do with trust. Mastering the language of science helped a generation of quacks trot out eugenic fantasies. Narrative is power: narrative is morally fraught.

Pretend, for a moment, that we perfect narrative-fluency pedagogy. We’ve figured out how to teach every student to distinguish fact from fake, analyze arguments critically, and write (or record, or code, or perform) persuasive narratives of their own. Of course, only a subset of these students will enter professional fields that grant them a public platform. And only an idealistic subset of these will accept a life of financial insecurity to become journalists, teachers, or university researchers whose ostensible goal is to tell the correct story. The majority—and the most talented—of the narratively fluent will work at PR firms, undertake research in private industry, or serve as in-house legal counsel for multinational corporations. For narrative skill is highly fungible.

Setting the pace: at an elite prep school on Long Island, students learn to stay one step ahead of big media.

For a glimpse of a future in which narrative fluency has been thoroughly commodified, consider the media-literacy program at the Ross School, an exclusive prep school on Long Island. For $41,200 in yearly tuition, they get to learn about the “construction and deconstruction of media,” spar with bright young minds, and gain entry into the tightest social circles of tomorrow’s big media. Ross’s curriculum, and education journalist Alexandria Neason’s glowing review of it, demonstrates a familiar pattern in pedagogical change: elite private schools set the pace, and the rest of the education system plays catchup. Ross students are taking the best media-literacy courses from the best teachers before everyone else. They will retain a competitive advantage in the workforce for years to come.7

The pedagogy of narrative fluency upholds itself as an antidote to moral bankruptcy, but at best, it is morally neutral. While narrative intelligence may guide some to the right answers, for many students, it will become a marketable aptitude alongside the familiar twenty-first century skills of computer coding, tax minimization, and personal branding. (Indeed, these skills themselves rely on a command of narrative.) Educators teach their students about argument in school under the assumption that it will make them more objective, conscientious citizens. But once these students graduate, they find that the incentives are broken. There’s far more money in manipulating the masses on behalf of the powerful.

Good luck outsmarting them.

-

Alexandria Neason, “Students of Truth,” Columbia Journalism Review, winter 2019.↖